Questions and Answers

This interview was originally published in Sauren Blaney’s MA Thesis Research on Photozines.

I’m interested in why so many photographers chose to independently publish their works. Where does your interest and desire to make photozines come from?

I have always been a magpie, collecting different ideas and influences from album covers to protest posters, and loved the idea of creating my own self-contained works of art that could be read as a short story.

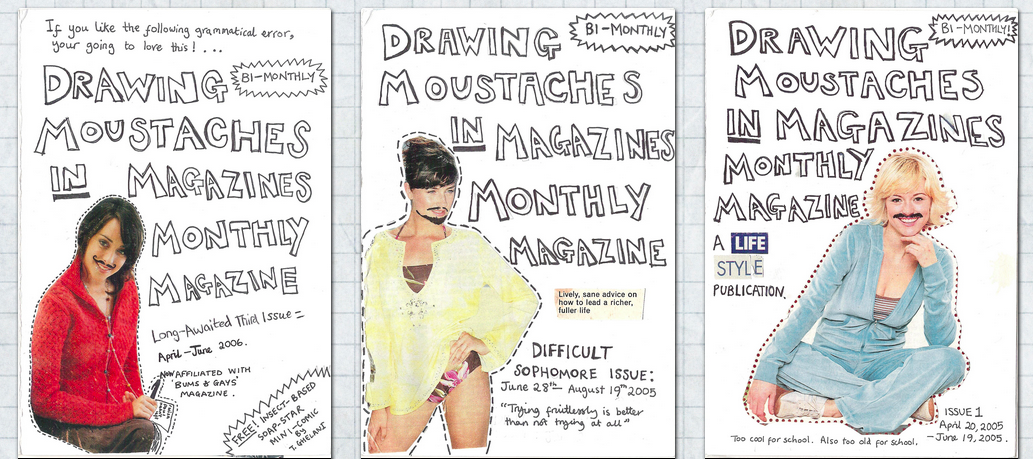

The comedian Josie Long first introduced me to zines and their place in DIY culture – how quick they ‘can’ be (I take ages) to design, create and publish. She produced bizarre and hilarious little photocopies booklets and sold them super cheap at gigs or posted them if you asked nicely, which was super inspiring.

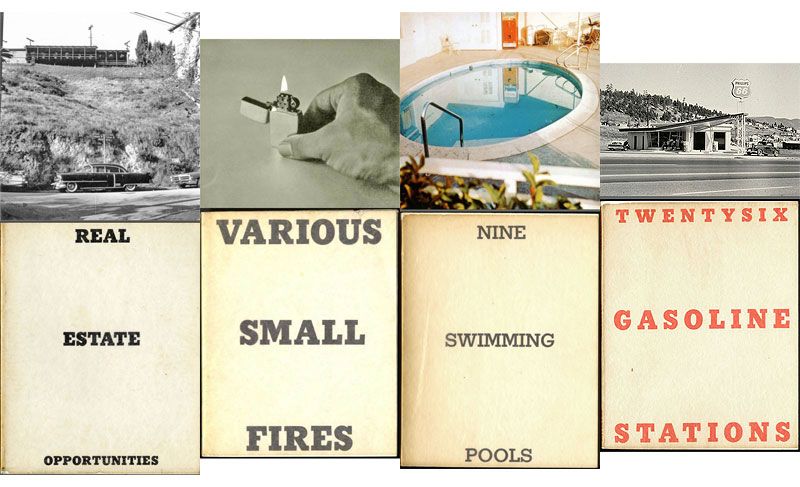

Shortly after, I saw Ed Ruscha’s pamphlets in Tate Modern and loved how weird they were and how much they annoyed both the art and photography scene by producing a series of objects that didn’t really fit either world. They were conceptual, funny, beautifully designed and seemed almost achievable.

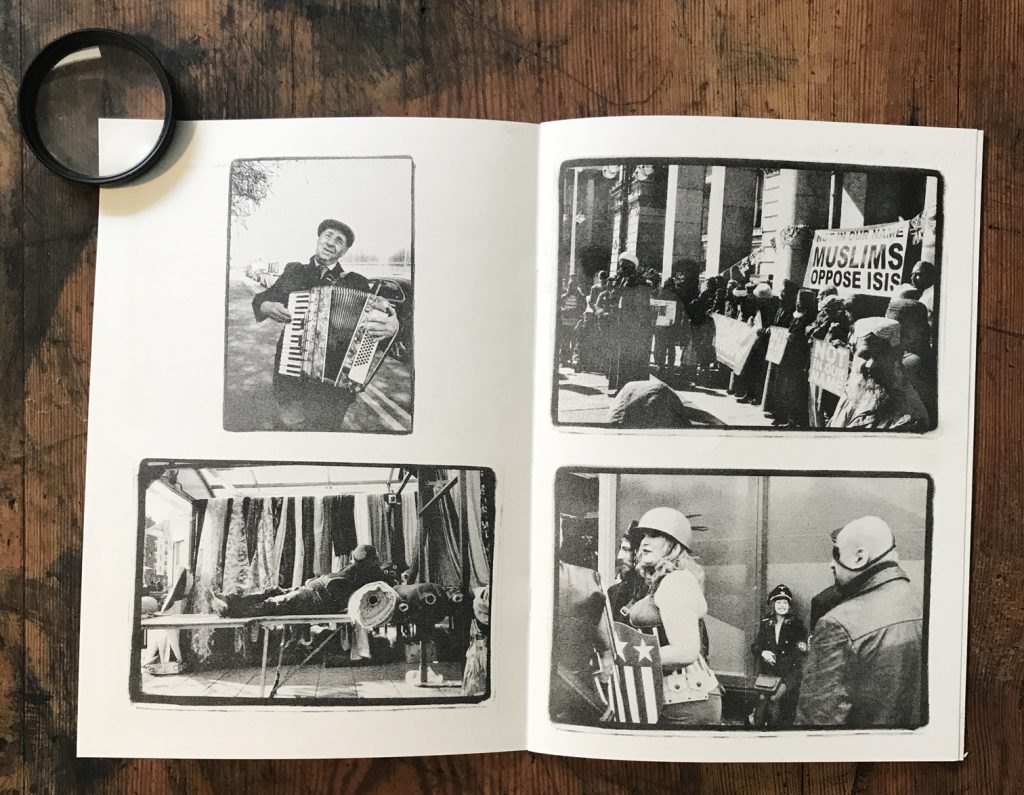

Zines are generally more informal and far less expensive than a photobook to produce, so sharing and swapping them with others is part of their DNA.

How important to you is the physical format and materiality of your zines?

It is very important to me that there is a tangible end product that someone can physically interact and spend time with. I have a completely different experience with a printed image as opposed to scrolling past it on a screen. I’m addicted to my phone and my day job is computer based, so having something tactile to work with is a kind of escape for me, and I hope it is for other people too.

Viewing photography on a device can be limited by size (some people’s negatives are bigger than the phones they are displayed upon) and algorithmically (trying to navigate the Zuckerberg machine is a Sisyphean task), so printing work in zines allows some control over one’s own means of production outside a set of rules no one really ever signed up for. I also just really like collecting stuff.

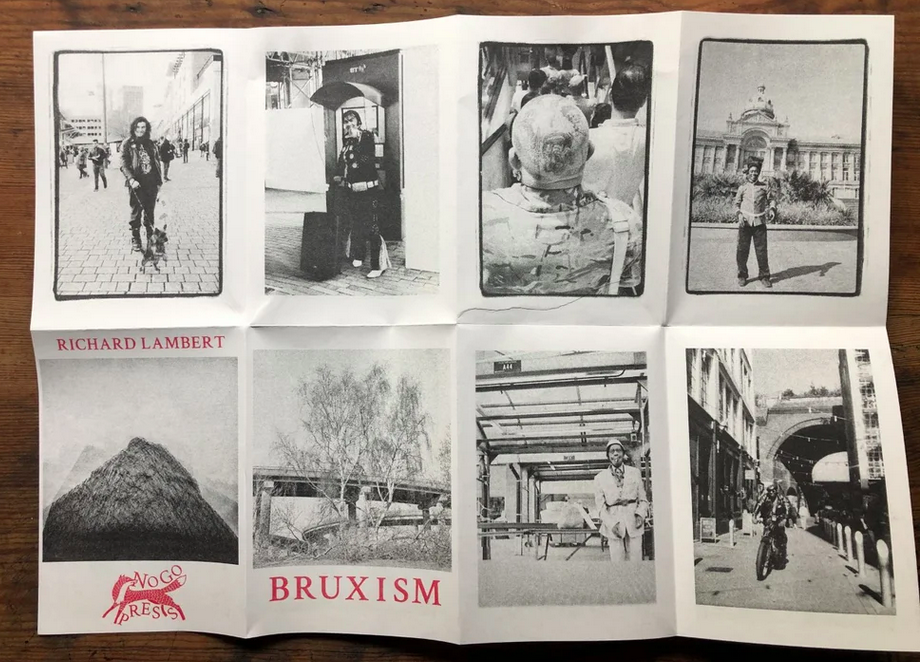

It seems to me your photography practice is innately connected to place. No Go, for example, centres around town in Birmingham. For you, is there a connection between photography, place, and perhaps publishing also?

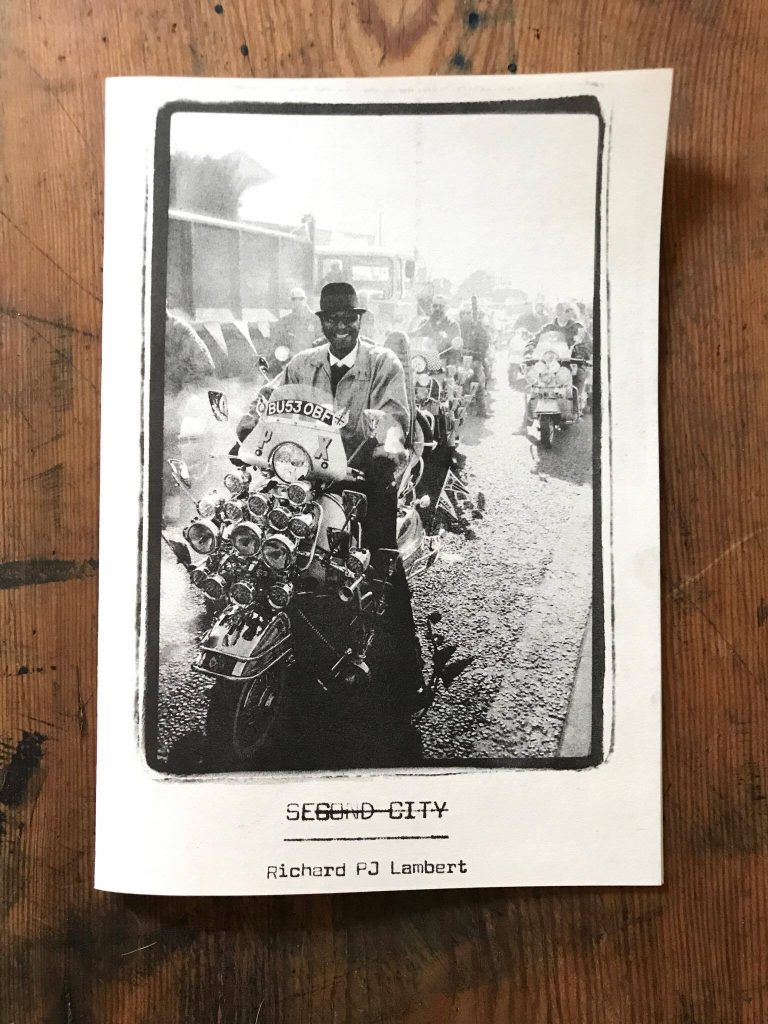

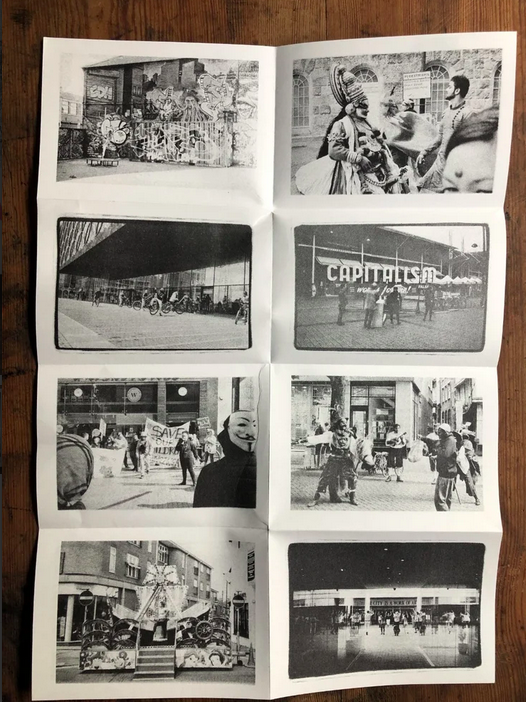

Walking aimlessly around cities is a favourite pass-time of mine and carrying a camera seemed like a natural extension of that. By paying attention to a specific location, especially a city with such a rapid pace of demographic and architectural change, one can capture not only serendipitous moments but cultural development over time. Birmingham is a constant work in progress, and it feels exciting to bear witness to that.

The name No Go Press is taken from right-wing cultural disinformation “news” pieces that have declared places I’ve lived in as ‘no-go’ zones. These lies stoke fear of the other, aiming to dehumanise the multi-ethnic population that makes our city what it is and pushes a fake, romanticised narrative of the past and what it means to be “British”. This is where I was born, grew up, worked and still live - I don’t ever mean to have a judgemental or didactic editorial voice, but anything I can do to counterbalance that conservative bullshit is a step in the right direction.

My only education in the arts came through courses run at a community darkroom (ran by the brilliant Dan Burwood and Andrew Jackson), which taught me valuable lessons on the local history of documentary photography. I was especially drawn to the work of Vanley Burke who recorded the Black British experience in the Midlands capturing everything from intimate portraits to Civil Rights protests. Phyllis Nicklin’s archive amazed me too – how she practiced a simple, honest and obsessive vision, using a vernacular which must have been seen as mundane at the time, but seem remarkably significant in retrospect.

Birmingham obviously isn’t a street photography epicentre like New York or Paris, but it does have its own idiosyncrasies that I believe are worth saving and sharing to get a better understanding of who we are, how we live and where we might be heading. I want to celebrate the people and places that make our home towns weird and interesting.

In a sense I see photozines as microarchives: they record, collect, and store images in a contained environment. At the same time, they’re incredibly personal, intimate and live through their distribution – the opposite of an archive. To what extent could you consider your zines a microarchive?

My photographic practice is self-taught and incredibly unfocussed, jumping between different genres and techniques in the hope a narrative thread might spontaneously appear after ruminating on them for years. This is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a terrible process.

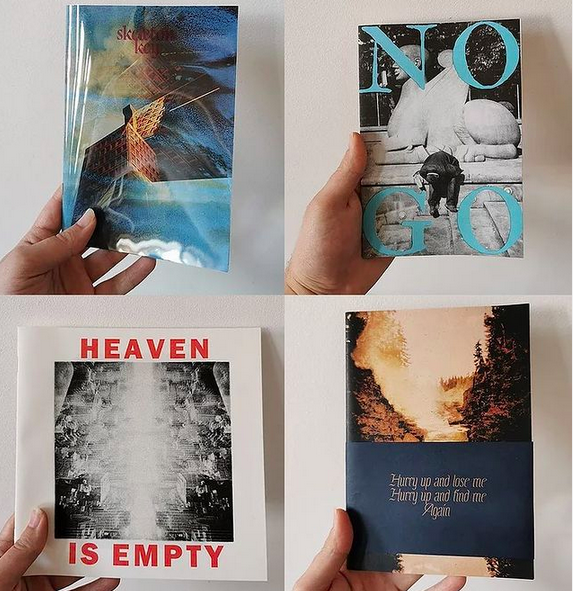

The idea of a zine as a microarchive, a container for these ideas, means I can sort of construct a project backwards. Selecting a concept, location, colour or a peculiar phrase gives me a lens to view and select my images to see what fits together and helps wrangle them into a coherent structure.

Would you be interested in displaying your work in a physical exhibition? Why/Why not?

Physical exhibitions and zine fairs are a good way to meet and talk with other artists and audiences, as well as having to think about one’s work in a different way. Pandemic allowing, there will be some kind of event to celebrate the release of new collaborative zine, tentatively titled ‘Homing’, named after the Liz Berry poem and my affection for pigeons.

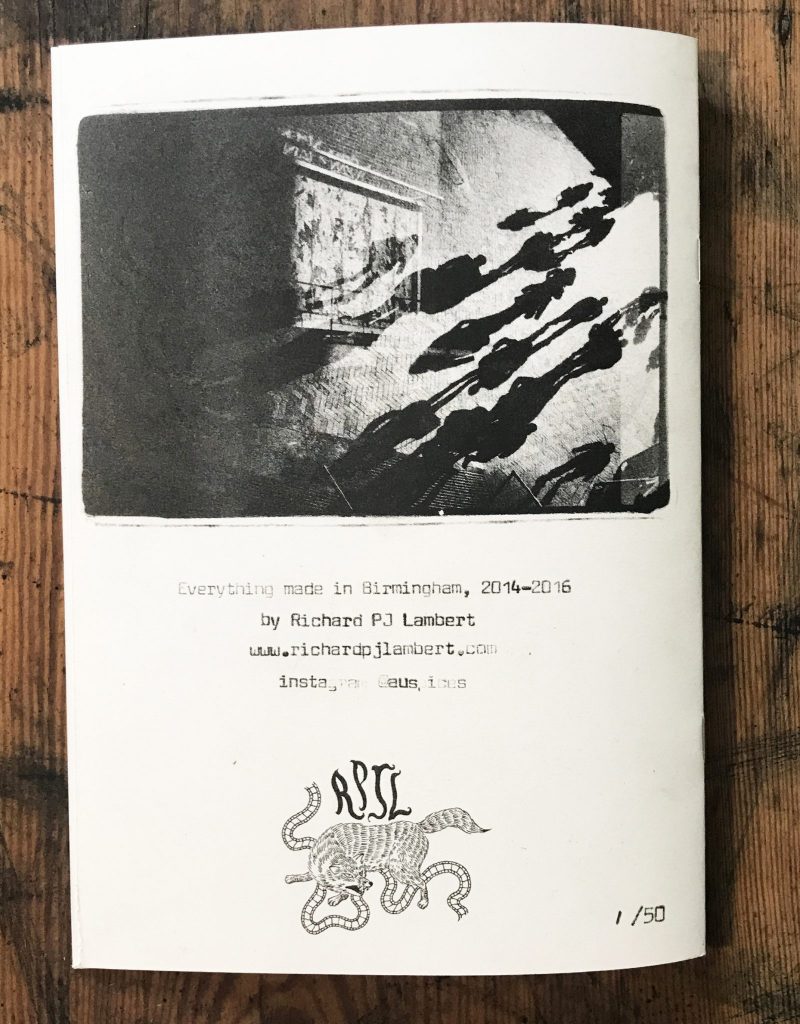

Can you tell me a bit more about No Go Press, what was your intention in creating it?

I wanted to help other photographers gain confidence and share the practical skills of creating, publishing and distributing their work. I will never forget how proud I was the first time I saw my images in print in a collaborative zine. At the same time, it also took me a year to make my first one, and it was only 16 pages long. If I could make this process easier for others and raise awareness of interesting voices from my local area, it would be a real achievement for me.

Many images produced in the West Midlands today either erase all our strangeness and problems, inviting gentrification over the threshold, or imagine the city as a terrifying depression-scape, emboldening hateful right-wing propaganda. I don’t believe that photographers should think like estate agents or act as peddlers of misery porn.

My intention is that No Go Press highlights unrepresented, exciting photography, and that the work finds the curious audience that it resonates with.